Stop Calling Kids "Lazy"

Our desks are in a square around the teacher. We’re reading nonsense Thai words so we can practice middle consonant sounds with middle tones. All twelve of us take turns, one by one in reading a list of essentially the Thai version of CVC words, except they hold no meaning.

The twenty minutes it takes to get to me seems like an eternity. I practice the CVC words as I wait, but it doesn’t take long for me to become distracted. I already know the letters of the alphabet at this point. My pronunciation is not perfect, but reading nonsense words is far too easy. When it’s my turn to read out loud to the class, I rush through the word list to get it done as fast as possible. My teacher makes me repeat roughly half the words because of my pronunciation. I let out a frustrating sigh, and read through them again. The broken tick of the air con and heat distract me even more. I feel that my pronunciation is even worse the second time around, but my teacher gives me a pass because we still have four other students to get through.

Many of my behaviors; distraction, rushing through work, and visible frustration are often what some would consider “being lazy”. In reality, I wasn’t lazy at all.

I was just bored.

tI’ve heard the word “lazy” get thrown around a lot in my years of teaching, and it’s almost always exclusively used to describe language learners. Learning another language is hard; it takes a tremendous amount of time, energy, and dedication to produce the amount language to get by on a simple day to day basis. Amplify that tenfold when in an academic setting. Language learners are far from being lazy – in fact, these are some of the most dedicated and hard working students that we have.

In my experience teaching, I’ve had my share of students who display these “lazy” behaviors. Really, though, it usually boiled down to a few key issues; engagement, confidence, and assumptions. Notice anything about those three items?

They are all behaviors that are influenced by the teacher.

Yes, I understanding learning is a two way street and that students do need to meet the teacher at some point, but it’s up to the teacher create an environment where that is possible. At the end of the day, we’re working with children. Expecting these children to simply comply is a lot to ask of them. Instead, teachers should inspire students to succeed and excel.

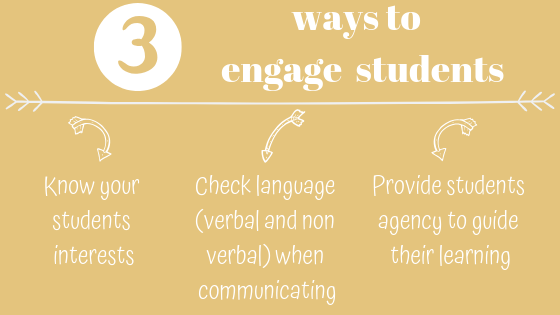

Below are some tips that have helped me reach the reluctant learners in my classrooms throughout the years of teaching. The potential ways to reach students is limitless, but these particular set of tips are ones that I typically start with.

It’s up to the teacher to create an environment where (learning) is possible.

This happens to be TESOL’s Principal 1: Know Your Learners (TESOL, 2018), and it’s instrumental in reaching students (especially those who are reluctant learners). Getting to know our students’ background shows that we care about them as individuals. This becomes especially important for our language learners who come from diverse home environments. Not only does it respect students’ heritage, but teachers also have the opportunity to learn something new.

It doesn’t stop at understanding more about students’ culture; we can get to know our students’ interests. Knowing what students enjoy outside of school can help us create more relevant learning experiences for them. For instance, one student in a G1 classroom happens to be an extraordinary writer. That is, when she wants to write. Writing brings up physical and emotional stress in this particular student to the point where even the simplest writing tasks become monumental challenges. One day, the class was writing an opinion piece (a prompt given by the teacher). Everyone had started, but her page was blank. Her body language told me that she was NOT interested in writing.

Getting to know our students’ background shows that we care about them as individuals.

Was the writing perfect? No – it didn’t have to be. Was it a start? Absolutely. These “gateway” topics that are geared towards students’ interests are the teachers’ “in”. Writing about Dragon-Mania is now her reward for writing different types of opinions. Simply getting her started has led to more impactful writing.

Side note: I’m currently playing Dragon-Mania so I can talk about it more thoroughly with this student. . .not because it’s actually fun or anything. . . >_>

Meet students where they’re at by creating multiple opportunities for students to engage in content material.

This concept is related mostly with mathematical problems; these tasks refer to providing access to content for students at all ability and comfort levels. However, I see this being a useful differentiation tool in all content areas. Meet students where they’re at by creating multiple opportunities for students to engage in content material. This entry point engages students at something they’re comfortable with, and that initial success makes it easier to attempt more complex tasks.

The spirit of differentiation is about creating multiple access points to content standards. This requires teachers to plan on tweaking the learning process, lesson content, or overall product for students with specific needs, but it also requires teachers to be flexible enough to react to students’ needs that may not have been anticipated.

We can communicate so much through our body and tone. Everything from simple gestures to the words we choose to convey information can change our messages entirely, whether we like it or not. With our students, the subtleties of our interactions can make or break relationships. People, not just students, can pick up on and react to these cues. For instance, in a classroom context, what message does it send when a teacher abruptly and forcefully directs students? What about an exasperated sigh? And the rising and falling of the tone of our voice? While teachers may not be explicitly vocalizing frustrations with students, body language can do it for them. Even the youngest of our students can pick up on these messages and inadvertently react to them.

Affective filter, a theory developed by Stephen Krashen in the 80’s, is the social – emotional aspects that come into play when learning. When our affective filter is high, we’re in high stress environments, thus out input and output (language or academic content) is low. When our affective filter is lower, we’re in lower stress environments, thus creating opportunities to increase both input and output.

If we’re producing negative language output, students can feel stressed and engage even less.

Instead of saying:

“You need to do _____.”

“Why aren’t you doing _____?”

“You aren’t doing what you’re supposed to be doing.”

Try saying:

“Let’s try ____ and then go from there.”

“How can I help you accomplish _____?”

“What do you need to get started?”

Affirming language can help students become more motivated, plus it sends the message that the teacher cares about them as a person.

This is my last resort when working with students who aren’t engaged in classroom activities. After exhausting all options, sometimes students continue to be disengaged. In this case, I’ve reached out to counselors with documentation of everything that I’ve tried. Sometimes things may be going on at home that are beyond our control. Counselors are experts in this field, so using them as a resource when needed could shed light on other ways we can meet the students’ social and emotional needs that may be holding back their academic progress.

———-

My hope is that teachers will consider these points before reaching the point of describing students as “lazy”. By creating engaging, relevant opportunities in the classroom, students can interact new learning in meaningful ways. Utilizing positive language instead of language laced with frustration can motivate students to reach the “high ceiling” that they are capable of. If we reflect on our practice and tweak the way we approach problems, we could truly utilize students’ full potential.

Recent Comments