Teaching Consent: Part 1

It’s my first week back in the classroom, and I’m already racking my brain for ideas on what my first blog post should be. My initial idea was to reflect on my experience going back in the classroom with my newfound knowledge of ELL best practice. Another idea was to share how I was priming my classroom as an “English immersion” environment. Another consideration was how my first day turned into a disaster and what I could have done differently (more on that in another post!).

Throughout the first week, I started to notice some curious behaviors and classroom dynamics. 16 out of 17 of my students went to Pre-K together, so they have had two years to form strong relationships with one another. This was evident in their level of comfort from day one: They’re excitable, enthusiastic, and love to touch.

Within the first thirty minutes of walking into class, I knew this was something I would need to address. These kiddos love to grab, push, hug, tug, poke, you name it. The amount of touching was so persistent I started to feel uncomfortable. Even though it was never out of anger or aggression, I knew that if it wasn’t addressed immediately it could escalate into a problem.

So we established our routines and classroom agreements. “Being Safe” was our number one rule, and we talked about how touching can compromise our safety. Still, the poking and groping persisted.

Within the first thirty minutes of walking into class, I knew this was something I would need to address.

It’s Not a One Off

We often teach the rule, “Keep your body / hands / feet / whatever to yourself” as a rule in isolation. It’s always been addressed in either gentle reminders or a direct, top down reprimand from the teacher. It’s dismissed with phrases like, “boys will be boys” without the adults in the room realizing that that actually perpetuates the behavior. Very little meaning is attached to the importance of our bodies and physical space. The more I realize this, the more I see it as a constant work in progress and not something that we only discuss at the start of the year. We live in a time where we know more about the impacts of our bodies and physical spaces than ever, so it’s up to us as educators to empower our students to feel comfortable with expressing themselves and owning their bodies, but also setting personal boundaries.

Consent is Beyond Verbal

“The absence of “no” does not mean “yes”.

In addition to the common, “Keep your body to yourself” rule, I’ve traditionally taught kiddos to say “ no” if you don’t like something someone is doing. While both of these are valid ways of addressing problems, I understand now that they may not work for everyone. This is especially true in Thai culture since problem solving may not always be so direct as a simple yes/no statement.

I experienced an example of this recently in my Thai class. Since I started teaching in the classroom again, I asked to change my Thai class from two hour sessions to an hour and a half. I asked my Thai teacher about whether or not to stick to the same price. I’ve been with this teacher for over a year, so naturally I felt comfortable bringing this very valid question up. However, it’s not very polite to speak so directly in Thai, especially when it comes to money in this type of scenario. I immediately saw my teacher’s body withdraw. Her eyes dropped to the floor, and the tone of her voice was much quieter and unsure. I knew immediately that I broached the unspoken rule of polite conversation, so I apologized and knew that I should pay the normal fee because typically her lessons aren’t any shorter than two hours.

Body language is an incredibly effective communication tool that is often observable before verbal output. For instance, how many times have you known the answer to a yes or no question before the other person even responded? Understanding this body language is learned, but never taught explicitly. We must learn through trial and error; by making mistakes and having various experiences with other individuals. I think that, by teaching students to read body language at school, we can bypass the trial and error phase and normalize respect for each others’ physical spaces.

The school counselor sent me a short cartoon encouraging kiddos to keep their bodies to themselves. It’s a typical cheesy video with a decent enough central message, and it also shows how different ways of touching can be harmful (for instance, one girl touches another girl’s headband without asking).

Image: WondergroveKids

We took time to analyze body movements as a way to give consent.

We took this a step further. I paused the video and zoomed in on one persons’ body language as someone was touching. I asked the students,

“What do you notice about her body?”.

Common responses were,

“She looks sad.”

“She looks upset”.

“She doesn’t look like she wants to be touched.”

“She doesn’t like it.”

We zoomed in on this further. I asked the students, “How do you know she’s sad/upset/doesn’t like it?”

The kids in my classroom are six years old and only one of seventeen are native English speakers. Instead of articulating their answer through words, they all mimicked her body language; they recoiled their bodies, scrunched up their faces, and put their hands out in front of them as if to push someone away.

We continued, “Did you hear her say the word no?”

The kids all nodded in agreement that she didn’t say anything at all. We then discussed how she is in fact saying no, but she’s saying no with her body.

The kids, who are very literal at six years old but have the capacity to think abstractly, were perplexed by this. The idea of using their bodies as a communication tool is something they do inherently, but naming it made it feel like a brand new concept.

Moving Forward

I already have ideas for how to continue our understanding of consent, and how it’s something to work on throughout the year. I haven’t explored these ideas yet (Week One of school only just finished) so I’m open for feedback and suggestions on ways to appropriately teach this. Here are some of my ideas:

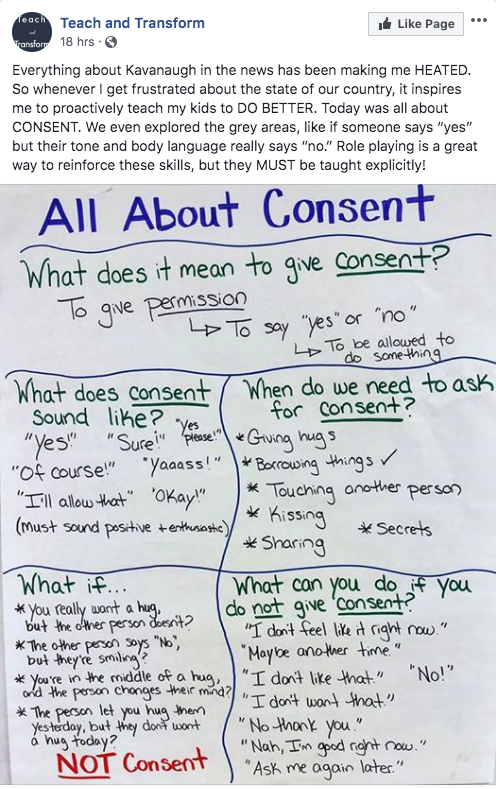

Normalize the Language

One of the first steps I need to take is to start conversations with the class. Liz Kleinrock (@TeachandTransform1) has an incredible anchor chart that she shared in a blog post about how she goes about teaching it. It’s an incredible read and relevant in any classroom. As Liz mentions, we already teach the foundations of consent by using rules like, “keep your hands to yourself” with our students, but naming this action makes it much more powerful.

Image: Liz Kleinrock Tolerance.org

Roleplays / Tableaux

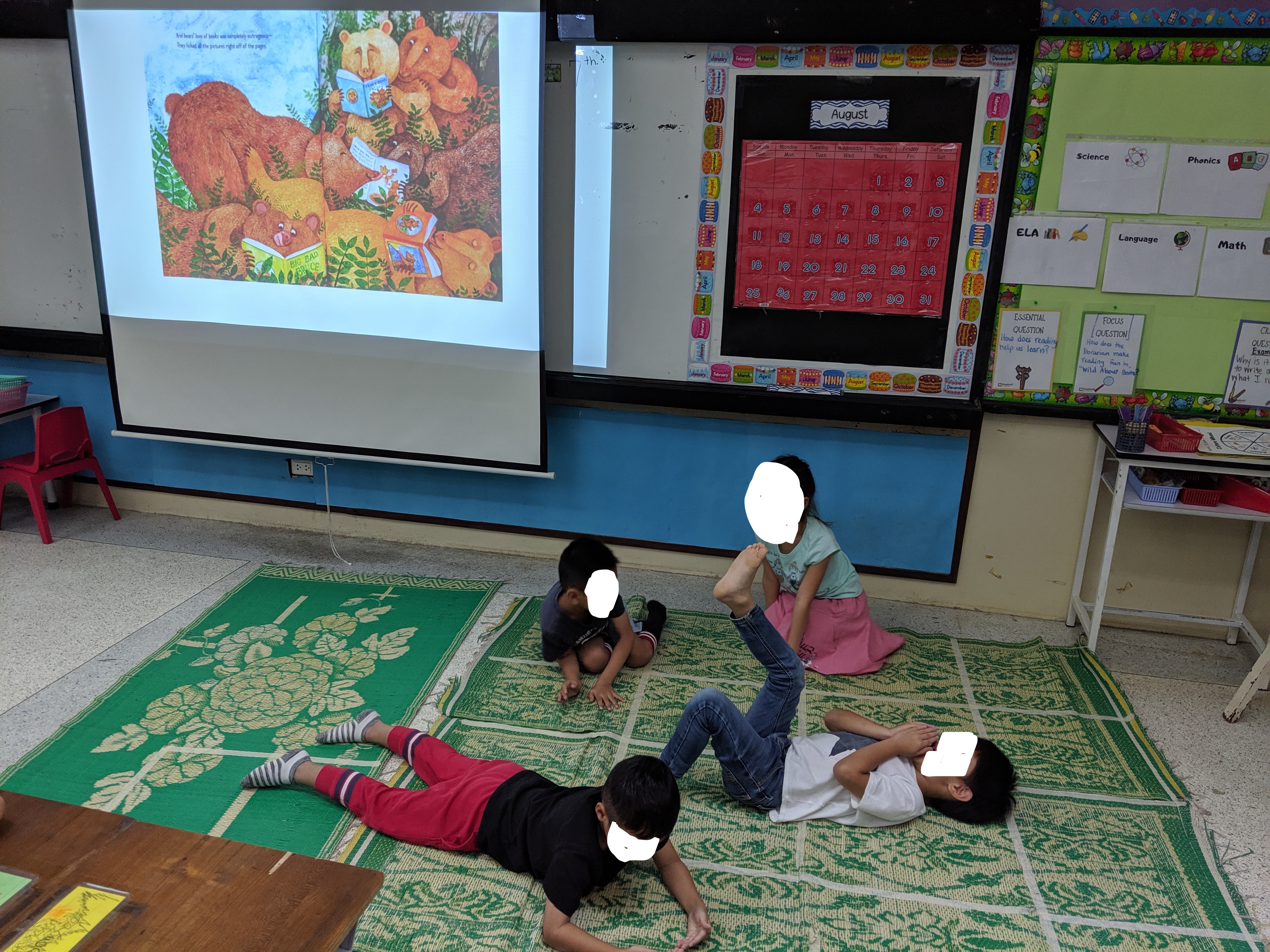

Roleplaying scenarios like these can be tricky. Sometimes, roleplaying as aggressors can enable the negative behavior. Instead, I’d like to try roleplays as practice for communicating with our bodies and responding to body language. For example, everyone can practice “Use your body to show that you don’t like something.” This way, no one is singled out as the “bad guy” and everyone can participate in a more neutral space.

I recently practiced tableaux with my students when acting out parts of a story we were reading. The kids ate it up. They loved using their bodies to act scenes with one another, and it gave spectators an opportunity to share their notices and wonderings. Tableaux is an effective engagement tool for teaching as well as a means to exploring concepts in a more unique way.

Image: My students using Tableaux to act out scenes from a story.

A Reflective Tool

I have plans to implement these pieces alongside the school counselor and colleagues passionate about this subject over the next few weeks. Myself and my Grade One cooperating teacher are slowly incorporating our Math / Science / ELA curriculum as we continue through the first month of school, so we have time to focus on classroom routines and and community building activities. I’m excited about the potential this has to change our classroom community, and I’ll be sure to share my experiences in a later blog post as well. In the meantime, please feel free to send more ideas my way!

Thank you for sharing what you are working on. You have inspired me to have similar conversations with my students this year.